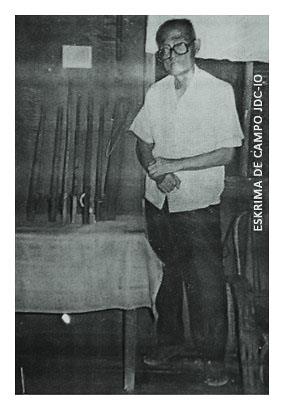

Grandmaster Jose D. Caballero

Ireneo "Eric" L. Olavides

Sometime in 1965, a friend introduced Manong Eric to Billy Baaclo. He went to Billy Baaclo house and asked him to teach him. And he did. They trained inside his house and nobody was allowed to watch. Billy Baaclo was an exacting teacher. Billy Baaclo lived in the pier area in Ozamis City. He was a World War II veteran whose USAFFE unit was attached to the US marine division in Bukidnon. During the Japanese occupation, he was a member of the guerilla force under Colonel Fertig. After the war, he worked in different trades; as a carpenter, police detective, clerk, bodyguard and finally a defense tactics instructor at the College of Criminology, Misamis University. He also gave private lessons in eskrima. Billy Baaclo was a very humble man. He never talked about his exploits during the war. Manong Eric only heard stories about him from the others. He was friendly and kind, but when provoked, he would simply say, "Try me if you will." He was a good role model for the martial arts. He taught Manong Eric for more than two years in the blade and stick art. He passed way about six years ago.

In 1968, a friend told Manong Eric that he should check out another eskrima expert by the name of Jose Caballero. His friend urged him to learn the man's style, De Campo 1-2-3 Orihinal. Naturally, Manong Eric inquired around before he sought Jose Caballero out. Manong Eric got two conflicting stories about the man. People who knew him well in his younger years said he was an exceptionally skillful eskrimador who had beaten a dozen well-known masters in juego todo matches. However, the feedback from his former students was very negative. And former students would advise Manong Eric to learn from other teachers. Manong Eric was intrigued. How could Jose Caballero be so, renowned as a fighter but none of his students were? There was only one way to find out. He went to one of Manong Jose's usual training locations in Ozamis, a residential place owned by one of his students. Unfortunately he wasn't able to chance Manong Jose that time so he talked to the house owner of his intention to learn from the old man. He gave his name and address and left the place with the hope that he will soon meet Manong Jose. After a few days, Manong Jose unexpectedly paid him a visit in his store and asked if he is indeed willing to learn from him. It was a story wherein the student SOUGHT the teacher and the teacher FOUND the student.

Approximately seven months passed and Manong Jose told him that he was done. Jose Caballero said that Manong Eric was already a De Campo eskrimador. Inwardly, Manong Eric was bothered. He felt that he had not learned as much as he could have. In a real fight, Manong Eric thought that his previous lessons from his other teachers would have served him better than the techniques of De Campo. He concluded that Manong Jose was holding back his best fighting techniques from his students.

(Grandmaster Caballero, the undefeated Juego Todo duelist in his prime, was also wary that anyone (even his closest apprentice) who discovered his shrouded techniques could some day become a potential challenger. There is no sparring in Eskrima De Campo since GM Caballero didn't want to play around exchanging strikes. His curriculum as Olavides described was too drawn out and consisted of generic Eskrima routines like the Abecedario, and the Espada y Daga X-block and strike. During their drills, Manong Eric observed that the old man moved differently than what he has taught him.)

Manong Eric became a regular visitor of Manong Jose on weekends. He brought bread, tsokolate bars for sikwate and other food to share with Manong Jose and his family. Their conversations inevitably steered towards the subject of eskrima. Manang Amparo, Manong Jose's wife, would proudly relate his exploits during these times. Sometimes, he would conduct review lessons.

One day, Manong Jose suddenly told Manong Eric that he could teach him the "specialization course" of De Campo for P300. This was what Manong Eric was waiting for. The course lasted six months. In the end, Manong Eric still felt that Manong Jose kept important techniques from him. When Manong Eric commented that his strikes seemed different and fast, Manong Jose simply told him that with practice he would also be able to achieve his skill level. Manong Eric kept his feelings to himself and never lost hope that one day, he might learn the real secrets. Manong Eric decided to continue his regular visits to Manong Jose's home. Early morning in 1974, Manong Jose came to Manong Eric's place asking for help. He needed some money to bail out his son who had been arrested by the police. The amount was substantial but Manong Eric offered it gladly. The son was released and eventually freed from the charges.

The next time Manong Eric visited Manong Jose, he asked him if he was really serious about becoming an eskrimador. He said he considered Manong Eric like a son and had decided to teach him his secrets, under one condition. Manong Eric had to be willing to represent De Campo in any juego todo contest in the future. A shiver ran up Manong Eric spine. It was a frightening condition. It never crossed his mind to participate in any organized jeugo todo competition. Manong Eric asked, "Manong, do you really think I can become a good juego fighter like you?" Deep within Manong Eric, felt he was way out of his league. Manong Jose said, "I will prepare you for that."It was a great feeling to learn the closely-guarded techniques of Manong Jose and become a fighter like him, yet at the same time daunting. Manong Eric just put back negative thoughts about the future behind and plunged into the terrific training of a juego todo fighter.

During training, Manong Jose's personality transformed him like he was in another dimension. Manong Eric was carried with Manong Jose into that place where his training felt like he was in actual mortal combat. Every training session was an ordeal lasting two or more hours. Each session took Manong Eric a little beyond his perceived limits. There were lots of repetitions. Manong Jose's training motto was: "You train to live, not die. Suffer during training, not during a fight." After three years of intensive training, Manong Jose announced that Manong Eric was already fit and ready to fight.

One day, Manong Jose told Manong Eric that he had to prepare himself because in two years, they were going to his hometown in Ibo, Toledo, Cebu. He would arrange some of his eskrima comrades to test Manong Eric skills. He said that if Manong Eric passed, he was confident that he could face any juego todo fighter anytime, anywhere.

The old dread returned to Manong Eric. He was in a dilemma. He only agreed to Manong Jose conditions to fight for him because he wanted to learn Manong Jose's secret techniques. He never thought it would actually come to this. Yet, he could not go back on his word. Manong Eric had to fight and he did the only thing he could think of. He prayed for deliverance. It came to pass.

In 1979, Manong Eric heard that the well-known Doce Pares Master, Fernando Candawan had moved to barrio Burgos, Aloran, Misamis Occidental, which was 30 kilometers from his place in Ozamis City. For some undefined reason, Manong Eric wanted to learn Master Fernando Candawan style too. Manong Eric sought the permission of Manong Jose. Immediately, he knew that Manong Jose was displeased. Finally, he responded, "All right, give me a good reason why and maybe I will let you." Manong Eric had a ready answer at hand. He told him that his De Campo would be better if he understood how other stylist fought. Manong Eric gave a brief lecture that was straight out of Sun Tzu's military classic about knowing yourself.

Manong Eric trained with the multi-talented Candawan for over a year. Master Fernando Candawan was awarded the "Eskrimador of the Year" award by the Doce Pares headquarters in 1964. He was an amateur boxer and wrestler, and had black belts in Karate and Judo. Training with him was also arduous and Manong Eric always was drained at the end of each session.

Master Candawan noticed that the way Manong Eric moved revealed that he had prior experience in eskrima. Master Candawan asked Manong Eric about his background and he told Master Candawan about his uncle and Billy Baaclo, but Manong Eric never revealed his association with Manong Jose. He was very careful not to show the techniques of Manong Jose to anyone. Manong Eric learned to be courageous and persevering because Master Candawan was very strong. While studying Doce Pares, under Master Candawan Manong Eric spent endless hours developing long-range techniques to counter the "bull-charging" close quarters fighting style of Candawan. Manong Eric describes sparring with Candawan: "He was a brawler and focused with only one thing once you cross sticks: that is to charge close quarters at the expense of absorbing blows and immediately execute a disarm." One day, Master Candawan told Manong Eric that he was already an eskrimador. Manong Eric took that as a compliment.

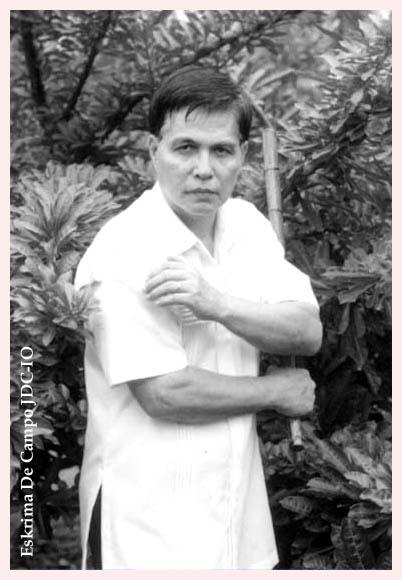

Ireneo "Eric" Olavides also holds a 1st Dan Blackbelt in Shorin-Ryu and for a while also studied Kok Sut with a former college classmate and confidante Antonio R. Ching. A consummate martial artist with an open mind, Manong Olavides has tirelessly researched and studied other fighting disciplines and philosophies. While the original written notes of Manong Jose are still being kept by his heirs, Manong Olavides later modified and simplified the ornate moves and retained the basic potent techniques; that until now are still being taught by Manuel L. Caballero in his father's hometown in Barrio Ibo, Toledo City. Of all his sons it was Manuel who inherited his father's natural fighting ability and grit. Compared to the original lessons, the present day De Campo taught by Olavides is the closest to the actual fighting style of his mentor. The reason behind this discrepancy is not because Manong Jose was a bad teacher. It was due to his obsession with secrecy that the techniques he taught were painstakingly veiled to hide the real deadly combinations. Grandmaster Caballero taught Eskrima to supplement his meager income as a coconut farmer. In order to sustain the enrollment, he programmed an extensive course that started at the elementary level, high school, college, instructor and master levels. Olavides zealously observed the subtleties of the old man's striking combinations when they trained. He eventually discovered that Manong Jose moved differently in fighting in contrast to what he did in exhibitions.

One time Grandmaster Caballero and Manong Olavides took a break from one of the bruising sessions with a treat of hot crispy bread and sikwate (native chocolate) that Manong Olavides never failed to bring along to please the old man. It was during one of these breaks that Manong Jose revealed in all candor that some of the silly stuff he taught was meant to camouflage the deadly moves he deployed during his Juego Todo heyday in the province of Cebu. What Manong Jose failed to document in his lesson plan, Manong Olavides took note and compiled. Manong Olavides later organized the salient moves of Grandmaster Caballero into groupings or sets of striking combinations. The present day De Campo has gone back to, its hidden roots that is simple, fast, intense and violent. Although Manong Olavides has modified and improved a large bulk of the striking mechanics of Grandmaster Caballero's method, Manong Olavides, in all humility, despite clamor from followers, refused to adopt another name and brand it as his own invention. With all due respects to the spirit Grandmaster Caballero, Fernando Candawan and Doce Pares, he is against putting any label to his style of eskrima. Eventually, Manong Olavides agreed to change the name of De Campo on one condition: it will only be named after the inventor. Thus as his ultimate tribute to Grandmaster Caballero, the method is now renamed simply as De Campo JDC-IO. With great hesitation he finally relented to have his initials attached to the acronym JDC-IO which means Jose D. Caballero and Ireneo Olavides.

For him, "style" is a unique individual character, and it can never be institutionalized or standardized. The vicious cycle has to end somewhere and giving due recognition, perpetuating and developing the original methods of the old grandmasters is the greatest achievement of a mature martial artist and gentleman. Until now he maintains that he is not worthy of the title Grandmaster. It is bestowed only to a few icons of the Filipino martial arts like his mentor Jose D. Caballero, Antonio Ilustrisimo, Floro Villabrille, Venancio "Anciong" Bacon, Ciriaco "Cacoy" Canete, Leo Giron, Felicisimo Dizon, Angel Cabales, Leo Gaje, Johnny Chiuten, Timoteo Maranga and Filemon Caburnay and the other great champions and innovators of our ancestors' warrior arts.. He is just a teacher and scholar of the Filipino martial arts, no more no less. Manong Eric as people close to him fondly call him is the antithesis of the eskrimador stereotype. Until this day he remains opposed to being called a Grandmaster.

A very amiable, humble and a God-fearing person, Manong Eric has remained reclusive for the past years and shared his art to only a handful of close acquaintances, among them was the late Edgar G. Sulite. His long hibernation from the martial arts scene was not a matter of choice but rather due to other personal commitments, occupational constraints and the environment that was not conducive to propagating De Campo 1-2-3 Orihinal. He has already retired from teaching Law Enforcement Subjects and Defensive Tactics at the College of Criminology of Misamis University yet he still continues to teach others to appreciate non-violence by understanding the consequences of violence. He is a volunteer worker in the Catholic Church ministry of evangelization.